(2/ )

2nd Iron Age [- 480/ - 50]

small molded bricks, Late 1st century BC - early 1st century AD

(3/ )

Modern period [1492 / 1789]

Vegetable Fiber (thatch or reed) was one of the earliest coverings used in gable roofing. The adoption of tiles in roofing was most likely motivated by the need to limit fires because of their fireproof properties. Archaeology has been able to document the use of clay, baked or glazed tiles, wood, slate, as well as stone or metal. The tiles are generally laid lengthwise and superimposed in the direction of the slope, although they can be matched to produce various geometric patterns. Most often nailed or hooked - as we can see in this example from the city of Nancy - in the case of steeply sloped roofs, they can also be fastened with screws.

(4/ )

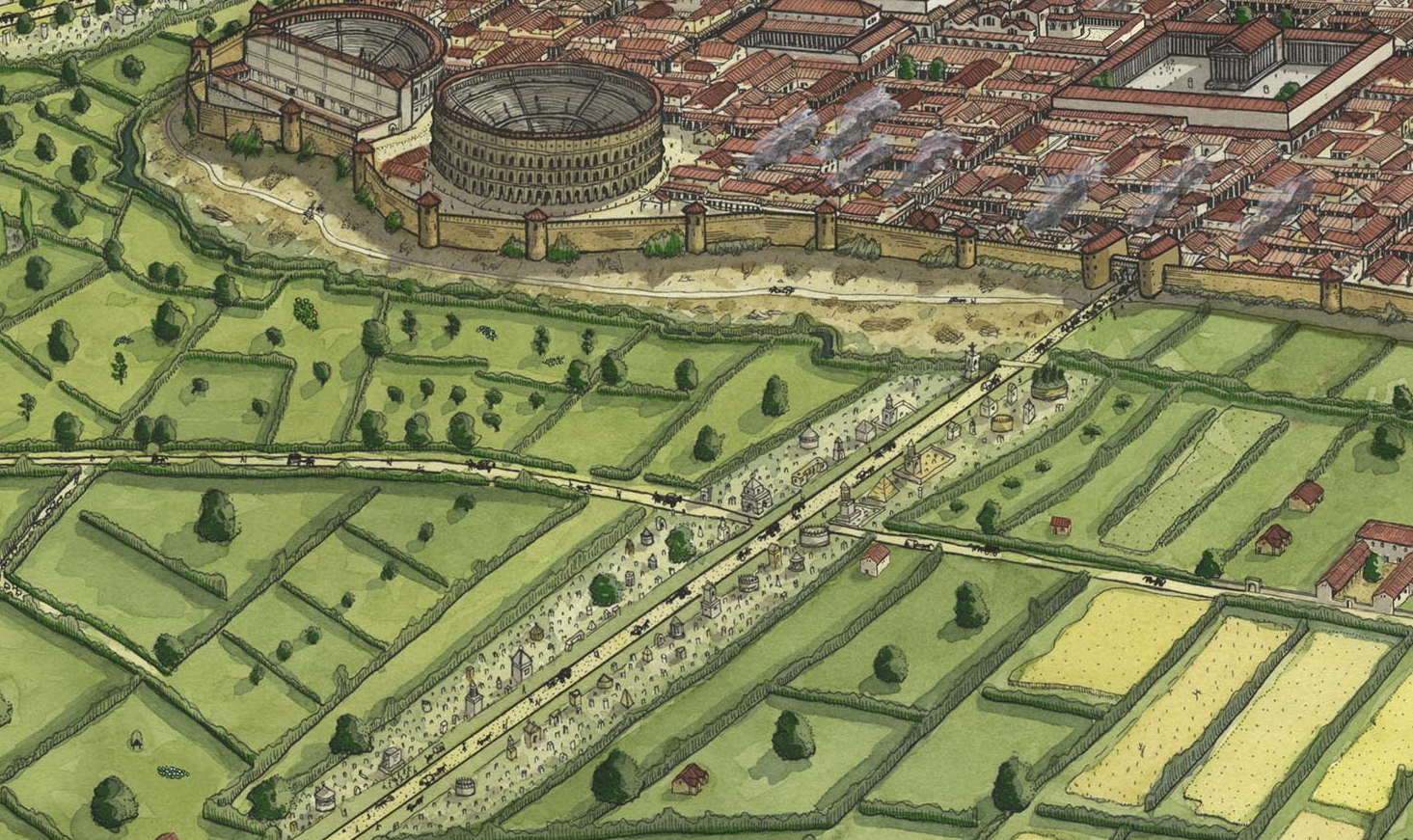

Gallo-Roman [- 50 / 476]

Iron carrier peak

.jpg)

(7/ )

Early Imperial [27 / 235]

This mosaic, discovered during excavations carried out in Nîmes in 2007, adorned the floor of a sumptuous Roman house (domus). It was executed using the Roman technique of opus tesselatum. On a first layer of pebbles (statumen) is poured a layer of aggregate of lime, gravel and stone (rudus), then a mortar of lime and debris of terra cotta (nucleus). Finally, on a thin layer of mortar, the decoration made of tesserae of 3 to 5 mm on a side is laid and fixed with a milk of lime.

(8/ )

Gallo-Roman [- 50 / 476]

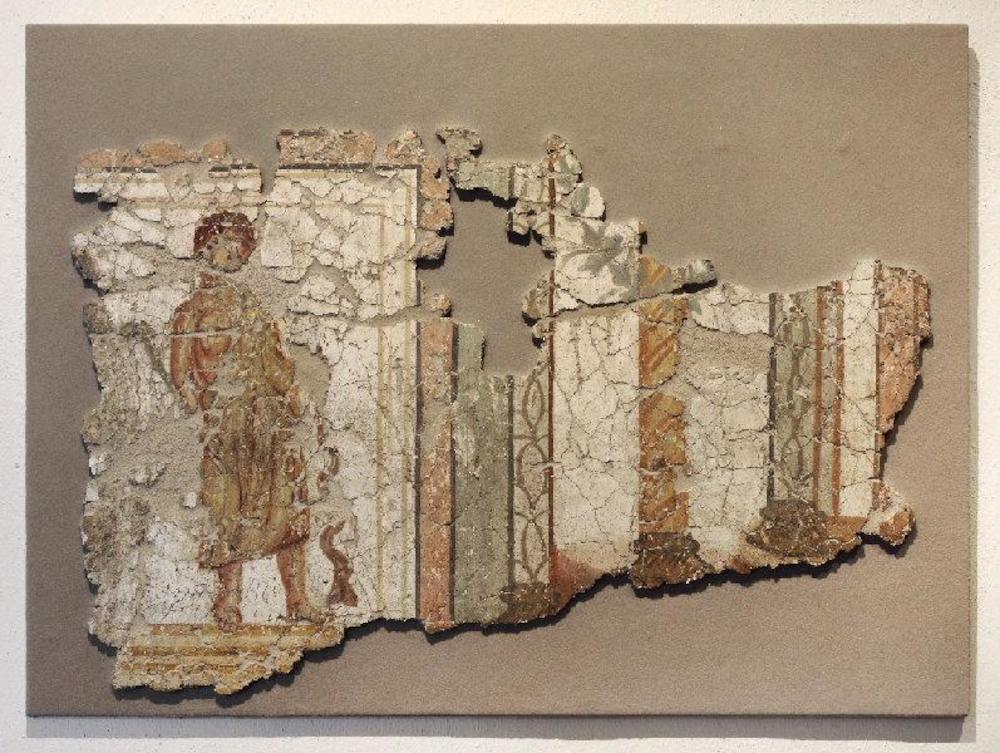

Discovered at the foot of Strasbourg's cathedral in 2012, during excavations of the Argentorate camp, this fresco adorned one of the houses of the six tribunes commanding the Roman legion. The fresco is a pictorial technique that assumes a certain skill and speed of the artist. After laying a wet plaster, composed of lime and sand, the painter must quickly apply the pigments before the surface dries, so that it absorbs the colors.

Learn more about Roman decor

(9/ )

Early Imperial [27 / 235]

The painted decoration of a room in the Xenia house was reconstructed thanks to fragments of plaster collected during the demolition of the building. The restored panel shows a still life painted on a small board with flaps and suspended by ribbons. It depicts a rooster, with its legs tied, on a shelf with two fruits; a jug decorated with a ribbon, two fish and a hare (on the right) are in the foreground. These are gifts of hospitality (xenia) offered to one's host, suggesting that this room was a reception or dining room. A white bird, perched on the frame of the painting, gives the whole a striking relief effect.

(10/ )

Early Imperial [27 / 235]

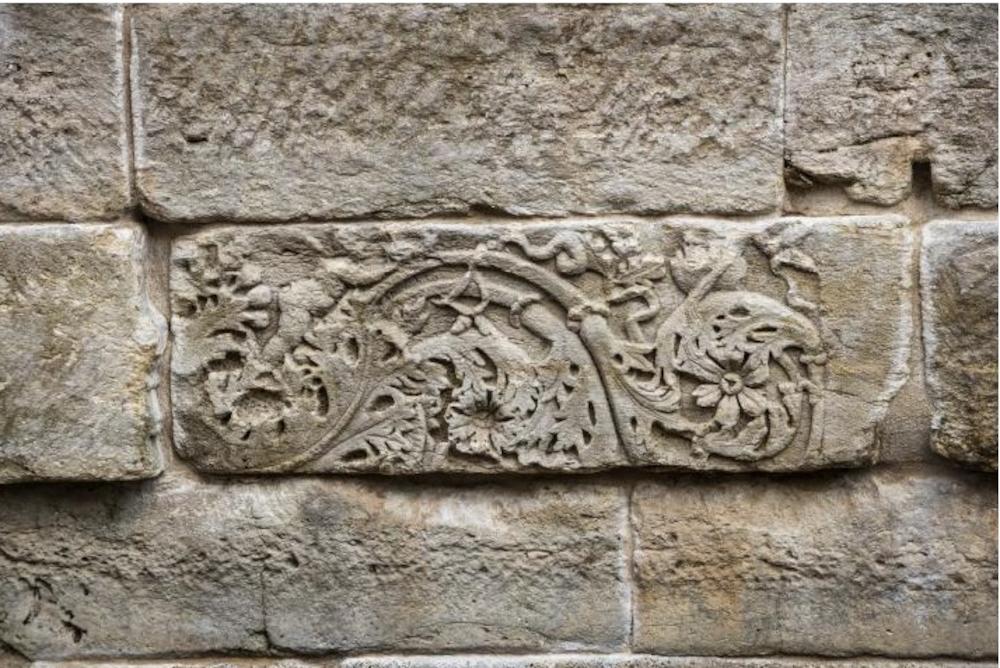

Throughout history, the reuse of architectural elements is common in construction. It allows for the construction and decoration of architectural structures at a lower cost, by replacing elements from buildings that have lost their meaning and therefore their usefulness. This architectural element from a wall on the Roman quay in Marseille was thus originally a relief decorating an early Roman mausoleum, located near a city gate.

(11/ )

Contemporary period [1789 / nowadays]

In 1937, France hosted the International Exhibition of the Arts and Techniques of Modern Life. Each country builds its own pavilion and the Soviet Union adorns its own with sculptures made by Joseph Tchaikov, a figure of Soviet realist art. In this architecture, which has become a work of propaganda, the eleven figures each represent an allegory of a Soviet republic and testify to the immensity of the country. Following the International Exhibition, the Soviet Union donated the sculptures to the Metalworkers' Union, which placed them on its property in Baillet-en-France. In 2009, excavations conducted in the park of the castle allow the rediscovery of these sculptures.

(14/ )

Protohistory [- 2200 / - 50]

"Grain mill composed of 2 parts: the fixed lower part or ""meta"" and the mobile upper part or ""catillus"". The two parts are made of two different materials (sandstone and granite)".

(15/ )

Modern period [1492 / 1789]

Circa 1520-1530 Avesnois limestone, traces of polychromy The identification of the statue was made possible by the presence of hooves on the left side of the figure's dress: they are the remains of a lamb, the attribute of Saint Agnes, a Roman martyr of the 4th century. The young woman is richly dressed in the fashion of the early 16th century. The sculptor has taken care to render the details of the garment such as the right sleeve or the jewelry. The work was originally enhanced with polychrome (paint applied to the surface). The flat back and forward leaning head indicate that it was placed against a wall or in a high niche. The orange-pink color visible on the garment is called a filler: it is a product that is applied to the statue as an undercoat, before the color is applied.

(18/ )

Early Imperial [27 / 235]

This architectural element was uncovered in the old city of Marseille, during the excavation of the former Alcazar theater. The remains found in this area range from the Greek period (5th century BC) to the contemporary period. This architectural element representing a tragic mask surrounded by acanthus leaves recalls the world of theater. It is one of a large series of monumental acroteria (corner elements of a roof) of the same type that adorned the tombs of the aristocracy of the Gallo-Roman province of Narbonne. Originally serving as a crowning decoration for a burial mausoleum of the 1st century CE, it was reused in a later construction. This tragic mask thus refers to the practice of reusing architectural elements from antiquity.

(19/ )

Early Middle Ages [476 / 1000]

This monumental tomb, known as a memoria, was located in the chancel of a single-aisled early Christian church built around the 5th century CE. The tomb is lavishly decorated with marble chancel slabs with originally polychrome scale decoration. Inside were two sarcophagi which in turn housed two lead coffins. Around the memoria, ostensibly placed in elevation next to the altar, were accumulated about fifty sarcophagi. This funerary practice is reminiscent of the medieval tradition of burial ad sanctos, i.e., near the saints who were supposed to grant the deceased protection after death. The local saints (not identified) are probably the two men buried in the memoria. Placed near an important communication route, this funerary church must have attracted pilgrims from all over early medieval Provence.

Discover an example of an ad sanctos burial ground

(20/ )

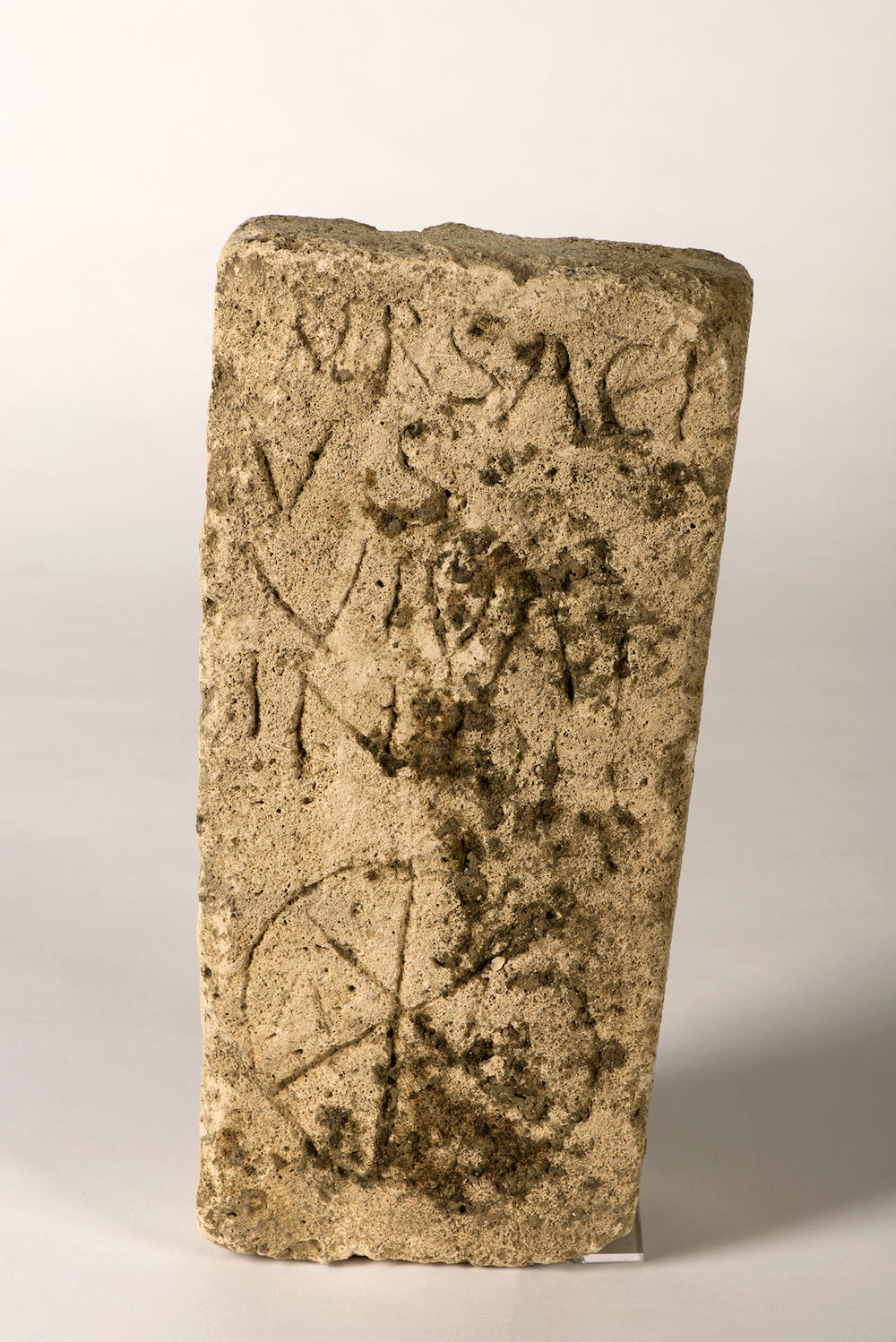

Early Middle Ages [476 / 1000]

Ancient and medieval burials could take much simpler forms than the monumental tomb or the grave placed inside the church. The vast majority of the population was buried in simple cemeteries, sometimes in sarcophagi. Erecting a funerary stele already required financial means since it was necessary to pay for the stone and the engraving. Very often, the stele alone constitutes the monument in memory of the deceased. This is the case with this early Christian epitaph from the first Christian cemetery in Laon. It is the funerary stele of a certain Ursacius. The Latin inscription, which surmounts a Chrism accompanied by the Greek letters alpha and omega recalling the beginning and end of the world, reads: VRSACIVS VIVAT IN DEO, "Ursacius lives in God."